interview – Text by Anika Meier – 12.01.2024

CLAUDIA HART: "I WANT MORE LIFE"

ANIMATION AND ORDINALS

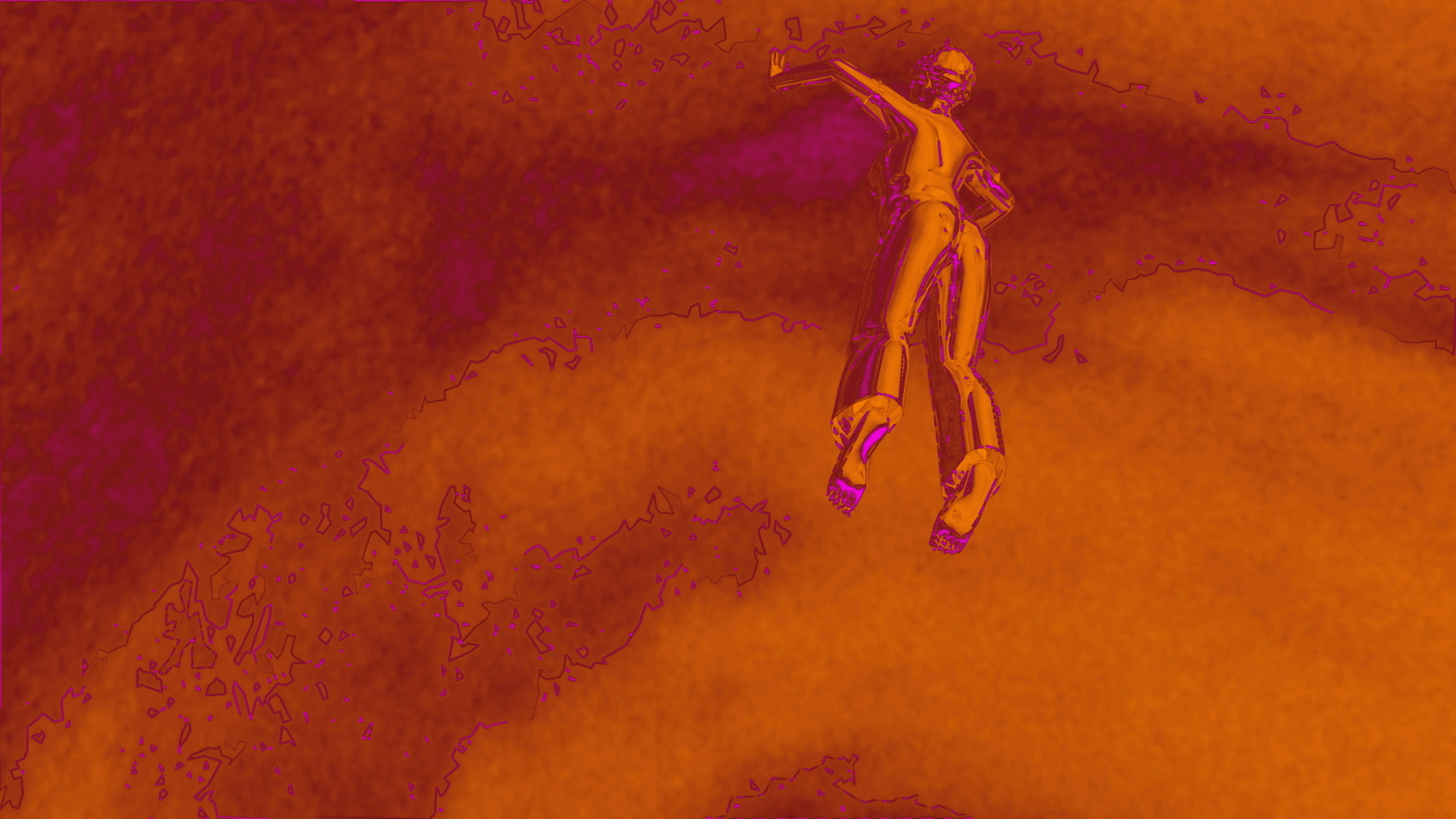

Claudia Hart's 3D animation MORE LIFE from 2000 is part of Sotheby's Natively Digital: An Ordinals Curated Sale. Bidding is open from 12 to 22 January 2024. Originally premiered in MOMA PS1’s ANIMATIONS, an early exhibition on CGI art in 2001, MORE LIFE underscores Hart’s continued interests in the political salience of the cyborg as a being that projects excess and challenges ideas of anthropocentrism, and in doing so, counters the techno-progressive, masculine, and extractivist dominions of technology.

Claudia Hart is an American artist who leverages simulation technologies to collapse the false binaries between human and avatar, artificial and real, mind and body. With a background in architecture and writing, Hart emerged in the 1990s as part of a generation of multimedia artists exploring issues of identity and representation. Drawing on computing, virtual imaging, and 3D animation technologies, Hart weaves together topics from art history, philosophy, and cultural studies to explore themes of feminism, embodiment, and temporality through symbolic poetics that stitch onto real-world politics.

Hart’s works are widely exhibited and collected by galleries and museums including the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, and the Albertina Museum, Vienna, The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, The Vera List Center Collection, The Borusan Contemporary Collection, The Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation Collection, The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection, The Goetz Collection, The New York Public Library, the Addison Gallery of American Arts, Andover, MA, The Richard and Ellen Sandor Family Collection, and many other private collections. Her work has been exhibited at the New Museum, produced at the Eyebeam Center for Art + Technology, where she was an honorary fellow in 2013-14, and at the Center for New Music and Audio Technology, UC California, Berkeley where she is currently a fellow.

In conversation with Anika Meier, Claudia Hart discusses fake books for kids and animation in the 1990s, a pink bear and Faust, and avatars and Ordinals.

Anika Meier: Claudia, what inspired you to start working on MORE LIFE in the late 1990s?

Claudia Hart: I began doing illustrated books in the mid-1990s. I hand-drew and lettered them. They were fake children’s books, but really for adults. I was inspired by “Maus: A Survivor's Tale," the graphic novel by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman, serialized between 1980 and 1991.

I was living in Berlin at the time. I moved when the wall fell and stayed for 10 years. I did two fake-kiddie books in Berlin, both inspired by issues that were important then and remain so. They were "A Child’s Machiavelli," that you exhibited at EXPANDED.ART last year, and "Dr. Fausties Guide to Real Estate Development," in which Faust, the central character from the Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 19th-century play, was reborn as a real estate developer who was also a pink stuffed teddy bear.

I didn’t know how to animate then, but inspired by TOY STORY, I decided to teach myself 3D animation. Dr. Faustie was my first avatar. MORE LIFE is my favorite animation from those early days.

AM: MORE LIFE shows a pink bear on a TV stuck in an elevator saying, "I want more life, fucker." Why that phrase?

CH: The audio clip is inspired by BLADE RUNNER, the 1982 movie directed by Ridley Scott, adapting Philip K. Dick's 1968 sci-fi classic "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" It was set in a dystopian future in Los Angeles that looked remarkably like the current Times Square, the center of New York, my home town.

AI-driven synthetic humans ("replicants") were bio-engineered by a fictional Tyrell Corporation to work on an imaginary space colony. When a fugitive group of advanced replicants led by Roy Batty (played by Rutger Hauer) escaped to Earth, a cynical cop, Rick Deckard (played by Harrison Ford), hunted them down. "I want more life, fucker," were the last words uttered by Batty before Deckard blew his computer's brain out. I think the words reflect the way we biological beings all feel, living our short lives in our fragile bodies, just struggling to survive.

AM: Where does the pink bear come from?

CH: The pink bear is Dr. Faustie, inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 19th-century character Faust. He is seductive and diabolical at the same time. That’s why he is so scary. He embodies the “evil doll” meme that appears in so many horror films. He was also very easy to model using the simple 3D animation tools available back then.

I was an early user of what is now called Maya, a 3D computer graphics software that was originally developed by Silicon Graphics Computer Systems and is currently owned and developed by Autodesk. At that time, Maya only worked on Unix operating systems while sitting on an expensive Silicon Graphics machine, which was not possible on a PC. MORE LIFE has a small pixel dimension (640 x 480 pixels, then "high definition") and is only 500 frames long. It also took about a week to render.

AM: MORE LIFE originally premiered in MOMA PS1’s exhibition titled ANIMATIONS, an early exhibition on CGI art in 2001. It was famously curated by Carolyn Christov-Barkargiev, the artistic director of dOCOUMENTA 13, in 2012. Why was she interested in MORE LIFE?

CH: This is only a conjecture, but I think Carolyn was interested in the line "I want more life" because it so much reflects the psychology of animators and the practice of animation in general. Animators are artists who live in their imaginations. We flee from the world and want our secret, imaginary worlds to be real with such fervent intensity that we believe we can actually breathe life into them.

Animation is very slow and labor-intensive, and animators are willing to spend a crazy amount of time bringing our worlds to life. We are like the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, the amorous sculptor whose marble stature came to life to become his bride. There was a famous book written in 1980 called "Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life" by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, early animators from the 1930s and 1940s, considered the Golden Age of American animation.

AM: It wasn’t just exhibited as a projection or on a screen in MoMA PS1. You had a special place in mind that matches the piece: the elevator. Why did you want to show the piece in an elevator?

CH: I was really naive when I chose that location! The MoMA PS 1 show was my first institutional show. Before that, I had exhibited paintings, sculptures, super-8 movies, and photographs in stagey configurations in galleries. I worked with the Pat Hearn Gallery in the East Village in New York for 10 years in the late eighties. With MORE LIFE, I wanted to make a site-specific installation reflecting computer "logic." Computers are code-driven recursive systems—systems that use themselves to build themselves. I wanted to show MORE LIFE in a small, enclosed mechanical room, in a small box (TV’s in those days were!), displaying the Dr. Faustie avatar sitting in a small box in front of a TV where he was sitting in a small box in front of a TV, ad infinitum. An elevator! I didn’t understand that NO ONE took the elevator at PS1, because it was only 2 stories high!

Carolyn offered me a much better position at the entry to the exhibition, but I insisted. I was very wrong. But I am very stubborn. I think if I had listened, my artistic life would have evolved very differently!

AM: MORE LIFE is both a tragic and an ironic comment on the virtual world generally and, specifically, the world of the imaginary, which is animation itself. It’s nearly 25 years ago that you created MORE LIFE. The virtual world has drastically changed over the past few years. What was your perspective on the virtual world back then and today?

CH: MORE LIFE is my plea for a more civil and humanistic world. In a world in which everyday people still struggle to maintain their dignity in a culture that has become increasingly technocratic, bureaucratic, and competitive. The science and technologies that we thought might liberate us from the limits of our fragile bodies have become more powerful and more advanced.

Perhaps it was equally true back when I made the piece as it is today. I was probably just too inexperienced and naive to understand that!

AM: Why did you now inscribe MORE LIFE on Bitcoin?

CH: I made my first NFT in 2021; it was already blowing up. I could only react to what was happening; I couldn’t just act, meaning I couldn’t follow my inner compass without the noise that comes from an active scene in the outside world.

Being early means chartering new territory, and to me, that means territory that is more open, more quiet, and more free.

My other reason is more practical. MORE LIFE is an early work and is very important to me. Because an Ordinal is encoded directly onto the blockchain, a work that has been inscribed can be preserved! With my early animations, which are so small and so short (out of technical necessity), it is a fantastic means of conservation.

AM: You consider MORE LIFE to be the beginning of your current installation-based 3D animation practice. What came after MORE LIFE?

CH: At the same time as MORE LIFE, I did two related projects. One was called SAVE ME, a forty-second animation from 2000 that I showed on a computer monitor and also on large public billboards in Louisville, Kentucky, produced by the Speed Art Museum. Later, I also showed them in Pittsburgh on public animated billboards, sponsored by the Wood Street Media Art Center.

Like MORE LIFE, SAVE ME is haunting, with a sad sound track of a laughing woman who also seems to be crying at the same time. The imagery is of an American suburban house, the sky raining happy-faced EMOJI. But in those days, there actually were no EMOJI! The HAPPY FACE meme had just hit and was everywhere. SAVE ME was also inspired by a movie, the David Lynch 1986 film "Blue Velvet," about a post-war America then reified as the fake-happy culture of Disney: oppressive, horrifying, and cloyingly sweet. An important early horror film.

At the same time, I produced a series of photographs of an avatar I called E, a cyber supermodel. They were photographic C-prints into which I integrated a 3D simulated avatar into alienating New York City street scenes in which contemporary flaneurs are pressed together physically yet cannot connect to one another emotionally, turning their eyes and being ineffably sad. Interestingly, I was just invited to show E in an exhibition in London at the Royal College of Art.

AM: Looking back at your early books and your first animations, and then looking at today’s NFT space, what has changed when it comes to creating art with technology?

CH: There’s something to be said for working in isolation! It suits me. I was a lonesome pioneer, and that meant that I had a lot of space and time to myself. The McCoys, who are also pioneers (and in fact shared the same page in the catalog of the ANIMATIONS PS1 exhibition where I first exhibited MORE LIFE) are now friends. I met Kevin for the first time when he helped me mint my first NFT for the Christie's auction.

When I started, I didn't know anyone else who worked with a computer except, most significantly, the Austrian media artist Kurt Hentschlager, who I later married and to whom I remain married (for the past 28 years). Kurt introduced me to his world—a world, I might add, that showed no interest in my practice (because I was a woman and because my work was and remains more personal, though I didn’t understand that at the time).

AM: What’s your advice for emerging artists working with new technologies who are getting told it’s not art or relevant?

CH: They always say that! I was told that my graphic novels and the giant watercolors that I also produced from their pages were also "not art." Yet they were gouache paint on linen! Not even acrylic.

AM: You started creating art in the 1980s and have seen many new technologies being used by artists. What are your predictions for the future of art and technology?

CH: Digital art will separate from digital design. It will become more personal, more expressive, and more emotional. It’s already happening!